Fabulous Fireflies!

by Enrico Nardone

Mark Twain once said that the difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug. His point is well made. But it leaves us with the question of what is the right word for the insects that make our summer nights sparkle? Twain referred to “lightning bugs,” but many of us call them “fireflies.” So which is the right word?

As it turns out, both are correct. They’re used interchangeably and refer to the same family of insects. Firefly is the elder of the names; it comes from England and its roots are centuries old. Lightning bug is an American moniker, coined sometime during the mid-1700s. A recent poll concluded that one-third of Americans use the name lightning bug, one-third use firefly and one-third use both names interchangeably. In Jamaica they’re called “blinkies” – maybe that’s a straightforward name on which we could all agree.

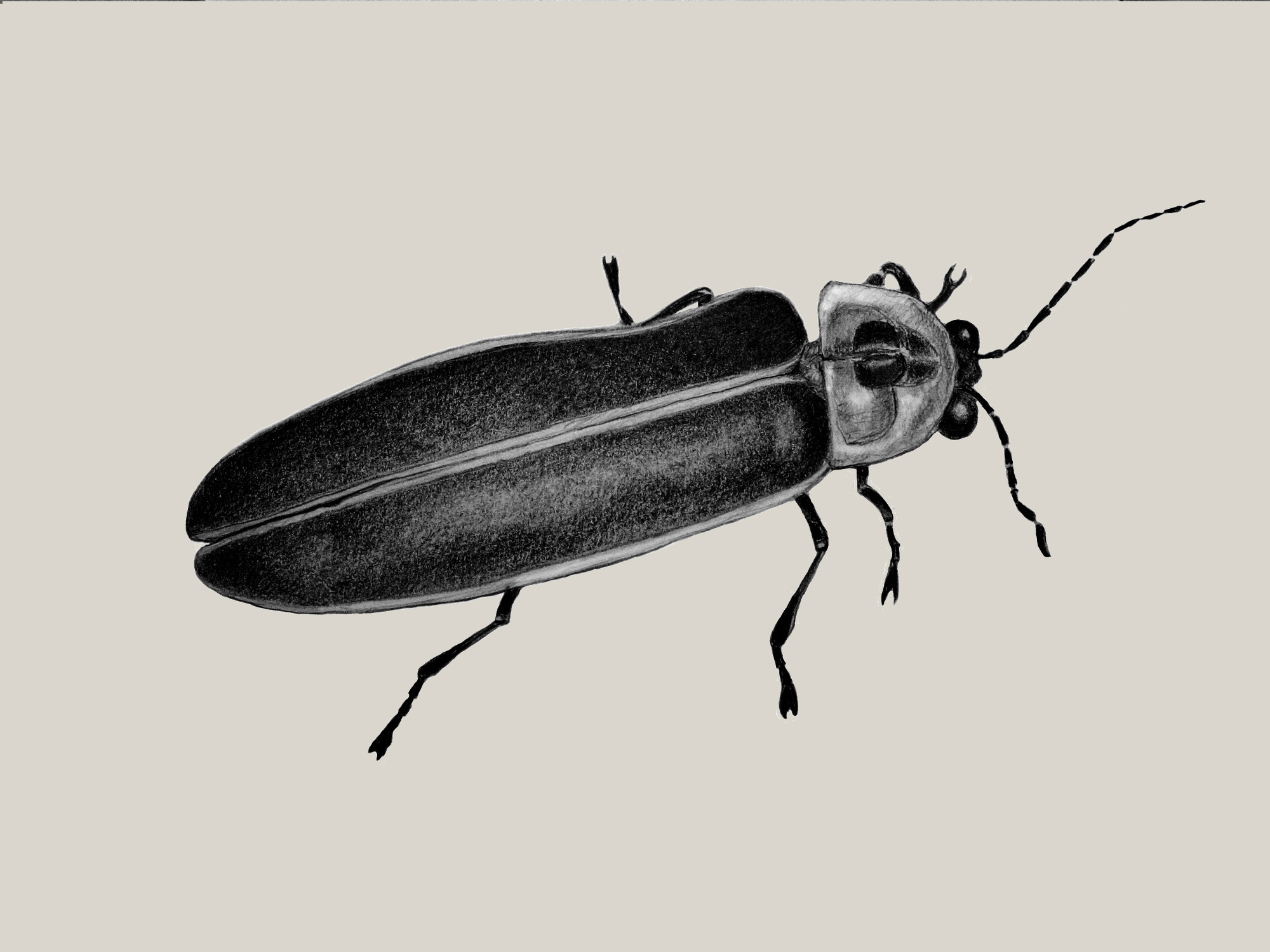

While the names lightning bug and firefly are both poetically descriptive, neither is scientifically accurate. Fireflies are neither true bugs, nor flies. They are beetles from the family Lampyridea, which translates to “shining ones” in Greek. There are almost 200 different species of fireflies in North America, most of which are found east of the Mississippi River. Surprisingly, there are no fireflies to be found west of the Rocky Mountains. Across the world, there are nearly 2,000 species; they’re found on every continent except Antarctica.

The fascinating thing about fireflies, of course, is the fact that they produce their own light (actually, only two-thirds of the species produce light as adults; but all lightning bugs do as larvae). It’s one of those amazing feats of nature that mesmerizes us as children and puzzles us as adults. So why do they flash and how do they produce the light? Let’s take the latter question first.

Despite childhood guesses about tiny lanterns or miniature flashlights, fireflies actually produce light through a process called bioluminescence. It doesn’t involve a spark or flame of any kind, just a straightforward chemical reaction. The light-producing cells (called photocytes) in the tail end of the bugs’ abdomens contain two unique chemicals: luciferine and luciferase. When these chemicals mix with oxygen, magnesium, and a fuel source called ATP, a high-energy reaction takes place that produces light as its byproduct. Fireflies control this reaction by regulating the amount of oxygen that reaches the photocytes.

One of the amazing things about this reaction is that it’s almost 100 percent efficient – that is, almost all of the energy is released in the form of light. There is no heat produced, which is why bioluminescence is often referred to as “cool light.” Compare this to the light produced by the bulb above your head. If it’s an incandescent bulb, only about 10 percent of the energy produced is in the form of light. The rest is wasted as heat, which is why these old-fashioned bulbs get so hot (and why you should switch to a more efficient compact-fluorescent or LED bulbs!)

The ability of luciferine and luciferase to create light in the presence of such common substances as oxygen and ATP (which exists in every living cell) has lead to many practical applications. The combination of these chemicals is used for a wide variety of medical and biological tests. NASA plans to use them to check for extraterrestrial life in space. They also have a more everyday application – they’re combined to create the glowsticks children love to wave around at nighttime events.

Until just a few years ago, the practical applications for these chemicals created quite a demand for fireflies. Chemical companies paid harvesters handsomely for the bugs and the rare compounds they contained. One woman in Ohio, known as the “Lightning Bug Lady,” collected more than a million each year! Such predation put a strain on local firefly populations, especially when combined with the constant pressure of habitat loss. Thankfully, scientists have learned how to create luciferine and luciferase in the lab, so the firefly trade has been put out of business.

But what about the other question: why do fireflies create their wonderful light? Well, like so many other beautiful displays and rituals in nature, it’s done for mating purposes. In most species, the insects we see flying around and blinking are males. They’re trying to locate and attract females, which are usually flightless, but climb to the top of a bush or blade of grass to do their (less frequent) return blinking. Males usually outnumber females by 50 to 1.

If a male and female are successful in getting together through their blinking communication, they mate and the female lays her eggs in moist soil. The eggs (which in some species have their own bioluminescence) will hatch into larvae in a few weeks. The larvae live in the soil and leaf litter for up to two years before building a mud cocoon and transforming into adults. All firefly larvae have luminescent abilities, usually in the form of a series of light spots on their sides (in fact, the larvae of some species are called glowworms). It is believed that this characteristic is used to dissuade potential predators (in nature, bright colors or showy displays often indicate toxicity or danger). The firefly larvae are voracious predators themselves, feeding on snails, earthworms and wide variety of other soil inhabitants. They subdue their often-larger prey by injecting a paralyzing chemical.

For many, fireflies are as synonymous with summer – as much a part of the season as vacations, swimming, watermelons and fresh tomatoes. Many of us are filled with nostalgia and joy at the very sight of their blinking light. They bring to mind warm summer nights with friends and family, chasing the slow-flying bugs around the yard with empty jars in our hands. Some of us gathered the insects with plans for bug-powered lanterns; others were just after a few nighttime companions for the bedside table.

Unfortunately, there is concern that the joys of fireflies may become a thing of the past. Their populations are plummeting around the world and scientists are scrambling to figure out why. We know habitat loss is a major source of their troubles, but light pollution is also being fingered as a culprit. Evidence shows that too much nighttime light can interfere with their blinking and the bugs’ ability to breed. While there are already a host of other reasons to support “dark skies” initiatives and to reduce unnecessary nighttime lighting around out homes, the plight of fireflies should give us a little extra motivation.

In the meantime, scientists continue to search for answers for disappearing fireflies. One effort, called “Firefly Watch,” by the Boston Museum of Science is looking for your help. They’ve set up a citizen-science survey that gives firefly lovers the opportunity to track fireflies in their own backyards and report findings on-line. It’s as simple as going outside a few nights a week and counting fireflies! The data will help researchers learn about the geographic distribution of fireflies and how human-made light and pesticides may affect them. To learn more visit Firefly Watch at www.mos.org/fireflywatch.

While the excitement of chasing fireflies may wane as we grow older, it’s a joy that quickly re-ignites when there are children around. It’s a special thrill to introduce a child to these magical insects for the first time, to see the wonder in their eyes as they try to comprehend the mysterious blinking lights, and to watch their excitement as they catch their first firefly.

So, if you can tear them away from the TV, mobile devices and video games this summer (firefly season on Long Island usually starts in early July), take some children outside as the sun is setting to enjoy one of nature’s best light shows. Find a relatively dark place just after sundown, arm them with empty jars, and introduce them to one of the great joys of childhood.